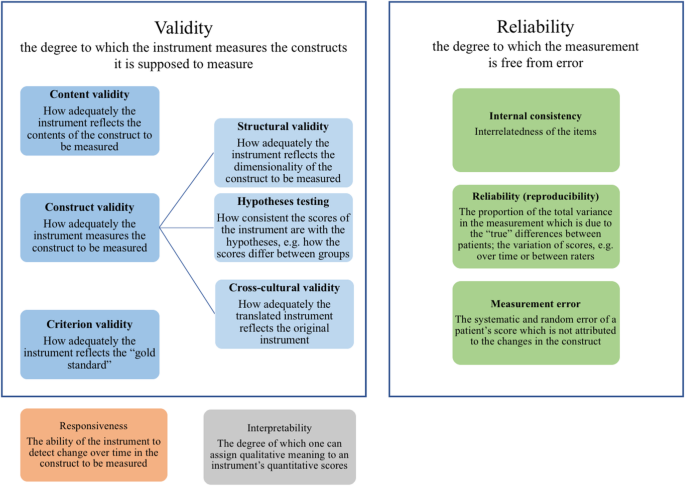

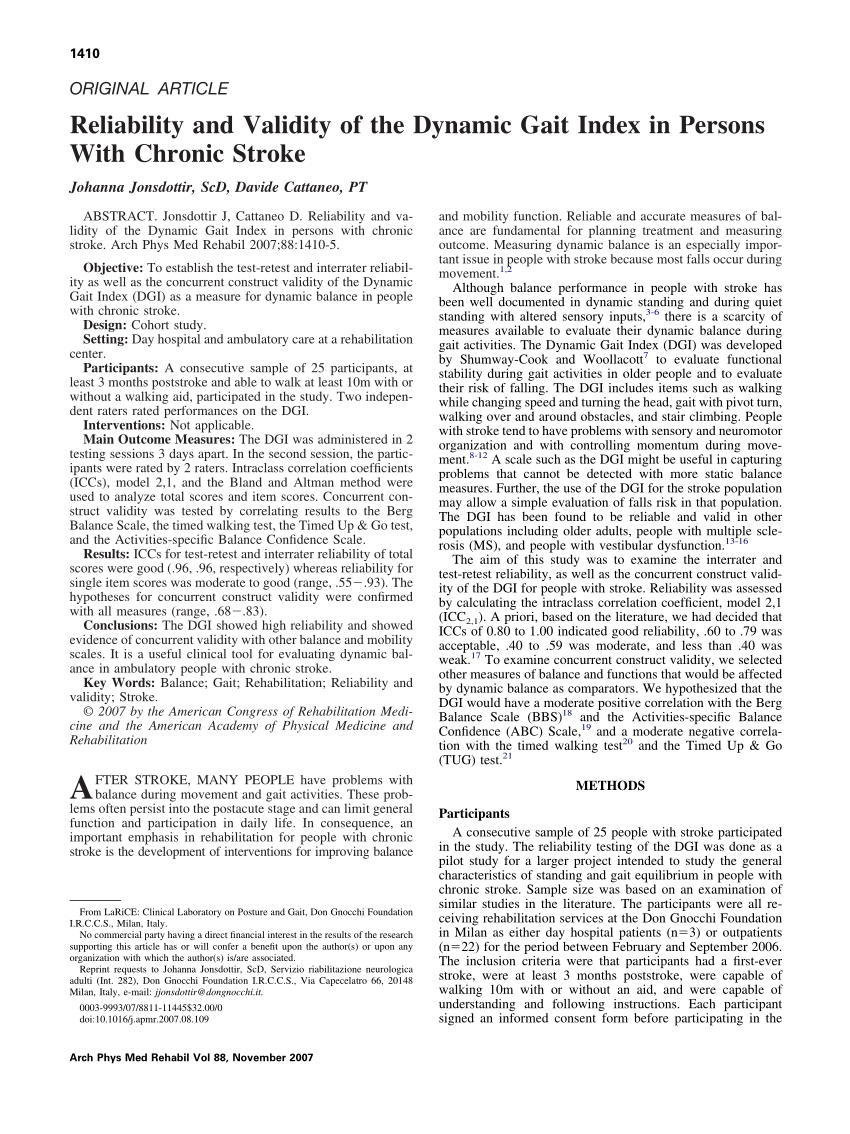

We also must test these scales to ensure that: (1) these scales indeed measure the unobservable construct that we wanted to measure (i.e., the scales are “valid”), and (2) they measure the intended construct consistently and precisely (i.e., the scales are “reliable”). Hence, it is not adequate just to measure social science constructs using any scale that we prefer. For instance, how do we know whether we are measuring “compassion” and not the “empathy”, since both constructs are somewhat similar in meaning? Or is compassion the same thing as empathy? What makes it more complex is that sometimes these constructs are imaginary concepts (i.e., they don’t exist in reality), and multi-dimensional (in which case, we have the added problem of identifying their constituent dimensions). For example, a survey designed to explore depression but which actually measures anxiety would not be considered valid.The previous chapter examined some of the difficulties with measuring constructs in social science research. In quantitative research, this is achieved through measurement of the validity and reliability.1 Validity is defined as the extent to which a concept is accurately measured in a quantitative study.

Hence, reliability and validity are both needed to assure adequate measurement of the constructs of interest.Figure 7.1. Finally, a measure that is reliable but not valid will consist of shots clustered within a narrow range but off from the target. A measure that is valid but not reliable will consist of shots centered on the target but not clustered within a narrow range, but rather scattered around the target. Using the analogy of a shooting target, as shown in Figure 7.1, a multiple-item measure of a construct that is both reliable and valid consists of shots that clustered within a narrow range near the center of the target. Likewise, a measure can be valid but not reliable if it is measuring the right construct, but not doing so in a consistent manner.

Nevertheless, the miscalibrated weight scale will still give you the same weight every time (which is ten pounds less than your true weight), and hence the scale is reliable.What are the sources of unreliable observations in social science measurements? One of the primary sources is the observer’s (or researcher’s) subjectivity. In the previous example of the weight scale, if the weight scale is calibrated incorrectly (say, to shave off ten pounds from your true weight, just to make you feel better!), it will not measure your true weight and is therefore not a valid measure. A more reliable measurement may be to use a weight scale, where you are likely to get the same value every time you step on the scale, unless your weight has actually changed between measurements.Note that reliability implies consistency but not accuracy. Quite likely, people will guess differently, the different measures will be inconsistent, and therefore, the “guessing” technique of measurement is unreliable. In other words, if we use this scale to measure the same construct multiple times, do we get pretty much the same result every time, assuming the underlying phenomenon is not changing? An example of an unreliable measurement is people guessing your weight.

Sometimes, reliability may be improved by using quantitative measures, for instance, by counting the number of grievances filed over one month as a measure of (the inverse of) morale. “Observation” is a qualitative measurement technique. Two observers may also infer different levels of morale on the same day, depending on what they view as a joke and what is not.

These strategies can improve the reliability of our measures, even though they will not necessarily make the measurements completely reliable. A third source of unreliability is asking questions about issues that respondents are not very familiar about or care about, such as asking an American college graduate whether he/she is satisfied with Canada’s relationship with Slovenia, or asking a Chief Executive Officer to rate the effectiveness of his company’s technology strategy – something that he has likely delegated to a technology executive.So how can you create reliable measures? If your measurement involves soliciting information from others, as is the case with much of social science research, then you can start by replacing data collection techniques that depends more on researcher subjectivity (such as observations) with those that are less dependent on subjectivity (such as questionnaire), by asking only those questions that respondents may know the answer to or issues that they care about, by avoiding ambiguous items in your measures (e.g., by clearly stating whether you are looking for annual salary), and by simplifying the wording in your indicators so that they not misinterpreted by some respondents (e.g., by avoiding difficult words whose meanings they may not know). For instance, if you ask people what their salary is, different respondents may interpret this question differently as monthly salary, annual salary, or per hour wage, and hence, the resulting observations will likely be highly divergent and unreliable. A second source of unreliable observation is asking imprecise or ambiguous questions.

Note here that the time interval between the two tests is critical. The correlation in observations between the two tests is an estimate of test-retest reliability. If the observations have not changed substantially between the two tests, then the measure is reliable.

Internal consistency reliability is a measure of consistency between different items of the same construct. The longer is the instrument, the more likely it is that the two halves of the measure will be similar (since random errors are minimized as more items are added), and hence, this technique tends to systematically overestimate the reliability of longer instruments.Internal consistency reliability. Then, calculate the total score for each half for each respondent, and the correlation between the total scores in each half is a measure of split-half reliability. For instance, if you have a ten-item measure of a given construct, randomly split those ten items into two sets of five (unequal halves are allowed if the total number of items is odd), and administer the entire instrument to a sample of respondents. Split-half reliability is a measure of consistency between two halves of a construct measure.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)